Minooka at War

Examining culture and events of MCHS during WWII

“It was a Sunday afternoon here when it happened,” she said. “I can remember sitting, listening to the radio and reading the fire papers as it came on the radio, and I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. The tone of voice made you think, ‘Oh yes, this is true. It’s really happening.’ And it was scary. It was very scary.”

The voice this woman heard was president Franklin Roosevelt announcing to the American public that Pearl Harbor had just been attacked by the Japanese. It was Dec. 7, 1941, when the nation was struck with anger and fear by the new threats. Patriotism skyrocketed, the Great Depression was no longer hanging over everyone’s heads, and the country soon found themselves sending men to both the Pacific and Europe in one of the most infamous wars in history. This woman knows this world war far too well because she lived through it.

She was a freshman at MCHS in 1941, even a member of the first Peace Pipe Chatter staff. Recently, she sat down with current Peace Pipe Chatter staff members and shared what it was like for a teenager growing up in rural 1940s Minooka, when the nation was at war.

She only had one condition: she wanted to remain anonymous. “I consider myself a private person,” she said. Typically, the PPC uses names when we quote our sources, but we will respect her wishes and keep her identification confidential in order to share the treasure of information she has given us. Throughout the story, she is referred to simply by pronouns or “The 1945 graduate.”

Her whole high school career occurred during WWII, and she recalls specific details on how it affected her hometown of Minooka. Before Pearl Harbor, most Americans were isolationists, wanting to avoid involvement in the bloodshed happening in Europe. The residents of Minooka, however, knew it was only a matter of time.

“What we were thinking was we were probably going to get sucked into that,” she said.

Verna Mae Bentson was her freshman classmate. In her diary on Dec. 7, Benston wrote, “I have an awful feeling tonight. Japan declared war on the U.S. today.”

After Pearl Harbor, it was apparent that the U.S. was on the verge of entering one of the deadliest wars in history. Patriotism boosted, and everyone was on rations in order to sacrifice for the war effort. The war touched every part of the country, including Minooka, and went on for longer than one might think.

“WWII lasted for years; it wasn’t just a couple of weeks when it was in the news,” the 1945 graduate said.

She also described the great anger everyone felt after the attack, and the support the young men had towards their country. The men lined up outside of the recruiting centers, ready to fight. Throughout the war, the PPC reported names of Minooka seniors who were enlisting.

“At that time, when a boy graduated high school, he probably went into the service that summer,” she said. “There wasn’t a whole lot of dating going on, either, just because there weren’t any guys around.”

Though most of the men were gone, some Minooka farmers chose to stay and help with the fields. The farmers, as she recalls, always had enough gas and a girl on their arm. High schoolers were also excused from war for a short period, which prompted students to stay in school.

Even with the men gone, the community still made great sacrifices that affected their everyday life. Necessities such as food, clothes, and gas were given in limitation. Minooka, however, was a very generous community willing to give even more.

“Everyone in the country sacrificed in some way,” she said.

The automobile industry had stopped making cars from 1942 to 1945, and instead made trucks, tanks and planes for the war. Scrap drives were greatly encouraged. Whether it was a simple tin can or a tire, donations were collected at multiple locations, including MCHS. Students could bring in these items to donate. In fact, as soon as they walked in the door, there was a pile of tin cans on each side.

School Life

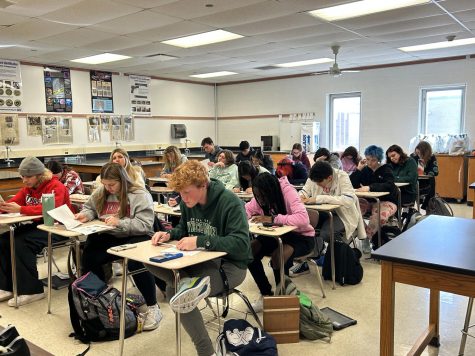

The MCHS of the 1940s looked very different than that today. High-schoolers did not go to the current building on Wabena Avenue, nor did the younger children walk through the doors of the junior high and intermediate school nearby like they do today.

During that time, 1st through 12th graders were located in the same building on West Church street. That building is now is part of the Primary Center. The enrollment then was so minimal, grades shared rooms: 1st-3rd grade in one room; 4th-6th in another; 7th and 8th together; and high-schoolers obtained the rest of the building.

“Minooka did not have a four-year high school until 1942, until then you could only go through your sophomore year,” Michele Houhens, a local historian at Three Rivers Library, said. “If your family was well off and you were not needed to work, you would go to Morris or Joliet to get your four-year degree.”

The 1945 graduate also attested to the drastic differences from when she attended the Minooka school to today.

“Each (class)room had their own coat room,” she said. “There were no lockers; there were just little rooms with hooks along the wall.”

In today’s era, it is a rarity to hear of a school having a basement. However, in the 1940s, this underground floor is where a lot of school events occurred. The basement was split up into two parts: a boys’ basement and a girls’ basement. When the harsh winters hit, that is where the children would play. Most likely due to lack of classrooms, the basement was also an educational setting for the high schoolers. In the boys’ basement, shop and science (which she said only involved biology, chemistry, and physics) classes were held. On the girls’ side, there was a home economics class, a typing room, and another little room that was held for Latin class.

“You don’t have [Latin Class] either, do you?” she asked.

“No, not anymore,” we said.

“You’re lucky,” she laughed.

Even though each grade only contained a few dozen students, the entire school body had to work around the lack of space. Gym class did not have a gym in the building. The main gym to the former high school building was not built until the 1950s, so the school resorted to holding gym class in an old barn. According to Houchens, this was located on Massasoit and Mondamin, about two blocks away from the old high school. It was common for the whole town to squeeze in there and watch Minooka basketball games.

Freetime Festivities

High school activities like basketball games offered an escape for the community, which had given so much for the war.

“The school at the time was probably more the heart of the community than it is today,” the 1945 graduate said.

The only sports at MCHS were basketball and softball for the boys. Girls wouldn’t compete at MCHS until volleyball debuted in 1973.

One of the favorite school activities for the teens were the dances; it was a time they could set aside the school work and have fun.

Swing music infiltrated any school dance students attended, as a number of clubs in Chicago would broadcast bands at certain hours of the evening. Without the luxury of TV or FM radio, the ability to explore a wide variety of music was virtually impossible. The community adapted to what they were given. As the 1940s period for music was labeled “The Big Band Era,” students listened to musicians such as Glenn Miller and Manny Goodman.

“There were more parties at school. Supposedly dances,” she chuckled. “The boys never wanted to dance. Some things never change.”

Even with the boys’ stubbornness, they still looked at the bright side of the night.

“At least we got to get out of the house at night. That was a big deal. Life was completely different then,” she said.They relied on community entertainment to satisfy their needs. Organizations around town would compose programs at the Masonic Hall in downtown Minooka, what is currently known as the Three Rivers Library. The movies in Joliet and the skating rink in Plainfield were the hotspots for the teenage population. What seemed like

an eternal amount of students would cram into the car of whichever friend was lucky enough to get the vehicle for the weekend and head off.

Trying to fulfill the role of a teenager in the heat of WWII proved to be a problematic task as rationing limited the supply of many daily household items, but most importantly, the availability of gas.

Often times, teens were left to make their own fun; things like TV didn’t exist yet.

Yet, if teens were yearning for a new scene, trains to Chicago traveled through downtown Minooka, whistles ringing within every nook and cranny of town to signal the train’s arrival and departure.

During her time at MCHS, she participated in an array of activities, including the Peace Pipe Chatter, in which she held the Editor-in-Chief position her senior year. Though she does remember much of her time working for the paper, she does recall the joy of interviewing all of the seniors her freshman year, getting their final words before they left.

The PPC itself has evolved in many ways since its first appearance in 1941; the cover was skillfully hand drawn and its few pages were a standard 8.5 inches by 11 inches in size. The issues were few and far between because with such a small number of students, there wasn’t much to cover.

The average 1940s MCHS pupil possessed scarce power over the clothing items they wore, ultimately abolishing their ability to express much sense of creativity with their outfits. With jeans frowned upon for males in the school environment, they were forced to resort to trouser pants. If they were seen without a belt on, an automatic detention would be presented to them. Females were prohibited to dress in pants of any sort and were required to settle for skirts instead.

“One teacher insisted that if the skirt did not reach the floor when girls kneeled then they were sent home,” she said.

A number of female students would manage to snag a buffalo-checked shirt from their dad’s closet in order to make an outfit pop.

Another way it was different was the livelihood of the students and their families. While most Minooka students today do not live on a farm, a lot of them did in the 1940s. Family came first, and if school was too time consuming, the student was often obliged to end their schooling and work full time on the land.

“It wasn’t uncommon at that time for 16-year-old boys to drop out of school to work on the farm,” she said. “It wasn’t because they were stupid; they had to stay home and help the family.”

Significant Sacrifices

During the war, the average American could no longer receive the luxuries of a full closet or abundant food in the pantry. To ensure that the army had all the supplies they needed to succeed, rations were put on the public, limiting what they could buy.

The 1945 graduate said shoes at the time were made of leather, which was a necessity to the fighters. Because of this, shoes were one of the main items rationed during the war. She recalls everyone only having just one or two pairs a year to accommodate to the frigid winters and smoldering summers.

A lot of food was also rationed, which included sugar, butter, and meat. While large urban centers such as Chicago were affected greatly by this, the woman said it wasn’t too much of struggle in the small community she grew up in.

“Small amenities actually got along better than people in the cities, because we weren’t as dependent on stores as they were,” she said.

Gardens, known as “victory gardens,” and the multiple farmers in the area that sold their cattle’s meat made living on rations slightly easier.

“We were lucky around here because there were still some farmers that churned butter and would sell it,” she said. “I think every house in town had a vegetable garden, and mom canned the extra vegetables so you had some in the winter time.”

The rations not only touched the people of Minooka, but also the school. The 1943 school yearbook reports the boys softball team only played three games “because of the gas and tire shortage.”

In addition to tin can drives, the school also held tire drives and iron drives. One detail of these drives that the 1945 graduate vividly remembers is that women were allowed to wear pants if they chose to work them.

The girls in the home economics club sent Christmas boxes — containing candy, cookies, popcorn, writing paper and envelopes — to former Minooka students serving in the armed forces. They sold milk to raise money for the project.

Although rations already limited the pleasures of Minooka residents, the generous people of the small village put others before themselves by often trading their rations stamps or giving them up for the greater good of someone else’s well being.

“We took care of each other,” she said. “We shared ration stamps, too. If you knew someone that needed them worse than you did, you gave them yours.”

Besides the ration stamps and scrap drives, the Minooka community’s vast empty lands also proved useful to the army. According to Houchens, the U.S. government had bought farmland south of Joliet in order to build an arsenal. Here, war weapons such as bombs were made. Because of this arsenal, the small town saw a wave of new neighbors as workers began to move in.

In addition, deep within the trees of McKinley Woods was a prisoner of war camp where captured German soldiers stayed immediately after the war. On June 26, 1945, about 100 German soldiers arrived, with another 150 on the way. The camp only lasted about two months before it was shut down.

Victory in Europe was announced on May 8, 1945. MCHS seniors would graduate 10 days later. The Japanese would surrender on Aug. 15. When American soldiers eventually arrived home with a major victory, the country couldn’t have been more ecstatic. Parades and carnivals were held in the streets to congratulate those who risked their lives.

The 1945 graduate remembers the support Minooka had towards the soldiers.

“There used to be a big sign over there by the railroad tracks where the park is now with the names of all the guys who were in service from here, and there were a few that had gold stars in front of their names,” she said.

Gold stars symbolized family members who had been lost in the war. But besides mourning those lost, there was still room for some joy, especially from the young ladies.

The woman recalls the multitude of weddings that happened as soon as the men returned home.

Love at First Late Bell

She had met her husband while they were in school. She had become aware of her future husband’s existence due to his superb talent of arriving to school late far more times than not.

“If I saw him on the street, I ran because I knew I was going to be late,” she said.

He was drafted into the war, and the couple failed to officially date until his several years in the navy had subsided. It just so happened that girl’s night out had been scheduled on the same evening of a guy’s night out — coincidentally, at the same location. The female members of the group had already tied the knot with the males, leaving one male and one female dateless. Naturally, to ease the awkward position the two were placed in, sparking a conversation was the only answer.

It is clear that throughout this troubling time of bloodshed and goodbyes, the residents of Minooka remained strong as a community and helped each other as much as they could. The war, in a sense, drew the town strongly together.

Near where the big sign with the gold stars once stood in Minooka is Veteran’s Park. Today at the corner of Wabena avenue and Mondamin street is a monument remembering those who lost their lives.