Fighting To Be First: Before Girls Had A Team

It took more than 30 years for girls sports to start at MCHS. Part 1 of 3

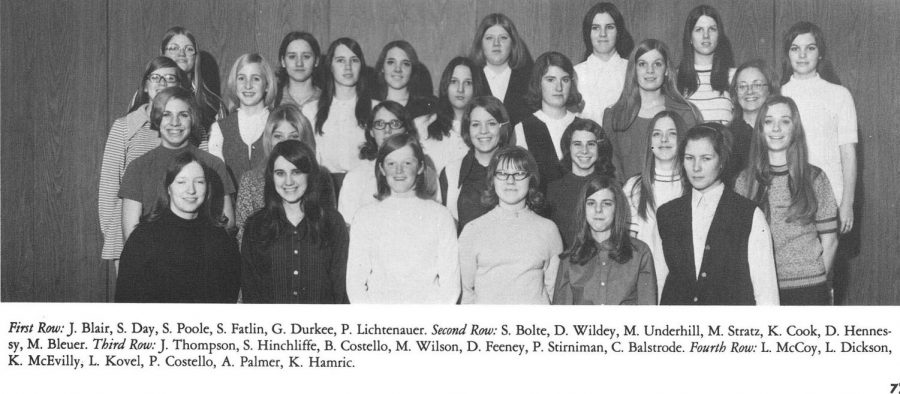

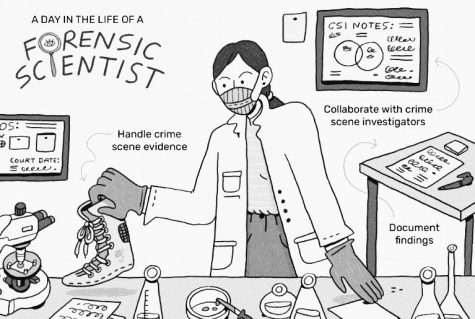

The Girls Athletic Club was one of the few athletic opportunities for girls at MCHS before 1973 when team sports began. This picture is of the Girls Athletic Club from the 1970-71 yearbook.

This is the first of a three-part story on the history of girls athletics at MCHS.

If only they could have some space.

A space to be heard. A space to play. A space to practice. A space to be a team.

“Back then we really didn’t think about it, truthfully.”

Wayne Greenbeck was a student-athlete at MCHS until he graduated in 1963. At that time, girls playing high school sports wasn’t on his radar.

“It’s not like the girls back then were upset they were not playing because it had been that way for so many years, unfortunately,” he said.

Cheryl Pillsbury began teaching English at Minooka in 1969. She would also coach cheerleading. “It was a man’s world both inside and outside the school,” Pillsbury said.

Perhaps the school fight song was the best example. Its earliest lyrics — back when Greenbeck was a student — began, “On you boys from MCHS.”

Knowing this back then made the progression toward girls sports that much more difficult. Many of the women, including Carolyn Kinsella, felt they were poorly treated and not given nearly as many opportunities as they deserved. Kinsella graduated from MCHS in 1973, a few months before the first girls sports would begin at Minooka.

“How can you say that women shouldn’t have sports if you never give them the opportunity to try?” Kinsella said.

Girls and women of this time felt not only that they weren’t getting heard, but also that they weren’t given the chance to voice themselves to begin with.

Kinsella noted that all the school board members at the time were male and there weren’t any women who led the school. She explained how men of that time never gave women that opportunity because “it wasn’t within the women that they knew.”

“A family friend who was also on the school board — and he had daughters — I remember him asking, ‘Carolyn, why would girls want to play sports? You don’t really want to, do you?’ It was beyond their comprehension that women could be competitive and athletic,” Kinsella said.

The men of that time may have not realized girls sports were a possibility. This might be the reason why it took so long for them to start.

Sherry Schmidt graduated from MCHS in 1971, the first graduating class from the current Central Campus building.

“Because I am a sports lover, I wish we would have had the opportunity to compete as a team against other schools,” she said. “I think we would have rocked it and brought home a few trophies.”

Had those opportunities existed for girls like Schmidt, she would have had a different high school experience.

“I was very athletic, so I would have played softball, soccer, and track for sure. I’m very lucky now. Our kids and grandkids are great athletes, and I can cheer them on,” she said.

Like in many aspects of life, if you were a female at Minooka before 1973, you had limited opportunities in athletics. You could be a member of the cheerleading squad, or you could participate in a one-hour, one-day-a-week afterschool athletic club. That was it. But when Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972 was passed, things began to change. Opportunities — and new challenges — arose for females across the country, including at MCHS.

Early Voices

In the beginning, there was only cheerleading. It began when Minooka became a four-year high school in the early 1940s. Girls first cheered for basketball. They then supported wrestling after it arrived in 1961, and eventually football after it started in 1971.

Pillsbury was the cheerleading coach in the early 1970s when other girls sports finally began emerging at Minooka.

“In 1970 to 1971, MCHS only had one squad of six girls for basketball and three girls for wrestling,” Pillsbury said.

The way they were chosen for the team was unconventional by today’s standards. Girls would try out while their peers watched and voted on who should make the team.

“I was not a fan of this procedure because it was more of a popularity contest than an actual tryout based on talent,” Pillsbury said.

The uniforms were handed down from year to year and later were made by the coach and a few moms. They were more modest than today’s uniforms, with longer sleeves and skirts.

In 1971, when Minooka got its first football team, the girls had more opportunities to cheer. Football and wrestling were coached by their new coach Ms. Joyce Tessiatore, and basketball was still coached by Pillsbury.

An Indian mascot also joined the cheer squad in 1972, the first being Charlie Lyons. Pillsbury said he was famous for his enthusiasm toward the athletes and cheerleaders.

One Option

The other athletic outlet for girls prior to Title IX was the Girls Athletic Club.

The Girls Athletic Club, or GAC, was a program for girls to play sports against their classmates. The club met for one hour once a week. They wore their gym uniforms. Sports like volleyball, soccer, and softball were like an extension of P.E. class.

“Our favorite was dodgeball, but during the good weather we made a soccer and baseball field,” Schmidt, who was the GAC secretary her junior year, said.

The club started around 1963. Depending on whom you talk to, it might be referred to the GAA, which stands for Girls Athletic Association. In 1965, participants had to pay 25 cents to join for the year, according to the Peace Pipe Chatter. By 1971, it was 50 cents. The sponsors of the club were female teachers.

They also held fundraisers, including bake sales. In 1965, the PPC reported the GAC sold “Minooka High School Stop Signs” for “loyal Minooka” fans. These were orange octagonal-shaped badges about 5 inches wide. They sold for a quarter. Throughout the years, the GAC also held a Father-Daughter Fun Night, a Mother-Daughter Banquet, and another banquet at the end of the year to celebrate accomplishments.

Besides being the only athletic opportunities for girls at Minooka, GAC and cheerleading had one other thing in common: competition for space to practice. There was only one gymnasium both at the old high school on Church Street and then again in the initial structure of the current Central Campus. When GAC was in session, the boys’ practices were pushed to an hour later.

“The boys were just livid, especially the basketball team,” Kinsella said.

When the girls were practicing, the boys would stand outside the doors and “catcall” them until their practice was over, she said.

“They had no concept that they should share that gym,” Kinsella said.

Cheerleaders would also have to practice in the gym, but only when the basketball team did not want the court, Pillsbury said. This rarely ever happened, so the girls practiced in the hallway often.

“The space was tight for doing acrobatics and building mounts, but there was no other place large enough to practice,” Pillsbury said. “The cheerleaders were determined to not let circumstances hold them back. And because of that, they were the best in our conference.”

Gym space would continue to be an issue, even after Title IX was passed.

IHSA Rulings

Some organized sports for girls did exist elsewhere in Illinois, although on a limited basis. Illinois had its own history of preventing girls from playing sports at the high school level. The IHSA is the governing body for Illinois high school athletics and has been since 1900 when it was known as the IHSAA.

“Decades before Title IX, girls basketball was even beginning to enter high schools in 1900; however, the early all-male leaders of the IHSA simply did not find girls sports acceptable,” according to the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library’s IHSA Oral History Project.

These leaders of the early IHSA were all men who shared the same common idea that sports such as basketball were not the typical stereotype of femininity at the time. They believed that girls simply did not want to play sports.

In 1907, the IHSAA banned girls at school from competing against girls at other schools. An article by Scott Johnson of the IHSA cites the IHSAA’s official report from 1907: “The game is altogether too masculine and has met with much opposition on the part of parents. The committee finds that roughness is not foreign to the game, and that the exercise in public is immodest and not altogether ladylike.”

The IHSA did allow interscholastic competitions for the individual girls sports of golf and tennis in 1927, according to their website, and in 1969 that they allowed interscholastic competitions for girls bowling and gymnastics. But team sports wouldn’t be allowed until the 1970s after Title IX.

One of the trailblazers who fought for girls sports in Illinois was Ola Bundy, who began as the assistant executive director of girls athletics in the IHSA in 1967. After Title IX passed, she was initially in charge of all of the state tournaments for girls. She was inducted into the National High School Hall of Fame in 1996 on her last day of work as an employee of the IHSA.

Passing Title IX

Title IX was a federal civil rights law passed in 1972 regarding safety from discrimination based on sex in public school activities.

The idea was pushed in the House of Representatives by Edith Green, a Democratic representative of Oregon, and in the Senate by Indiana Democrat Birch Bayr.

Bayr wrote the words that would become Title IX: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

In a nutshell, Title IX said that girls were given the right to participate in anything boys could without hardship or judgement. Both the House and Senate worked on separate bills before joining together in a Conference Committee to combine their ideas.

“I don’t know when I have ever been so pleased, because I had worked so long and it had been such a tough battle,” Green said, according to her House of Representatives biography.

The deadline on this law wasn’t clear, so it took some time for all schools to begin following in suit.

“Title IX happened. We were all jazzed,” Kinsella said. “We thought they would have to bring in girls sports.”

New programs for girls athletics would start at MCHS in the fall of 1973, a few months after Kinsella graduated.

Part 2 of this story was published on Thursday, Nov. 19. You can read it HERE.

Susanne Madding • Sep 30, 2023 at 9:04 am

Fantastic story! Thank you for chronicling our school’s history of girls athletics!