Fighting To Be First: Closing The Gaps

After establishing girls athletics, programs push for success

This is the final part of a three-part series on the history of girls athletics at MCHS. Read part one here and part two here.

Gym space wasn’t the only issue of equality once girls sports started at MCHS.

“The girls and the female coaches were fighting an uphill battle to be seen as an equal part of the sports program,” Glenda Smith, who began teaching at MCHS in 1976, said.

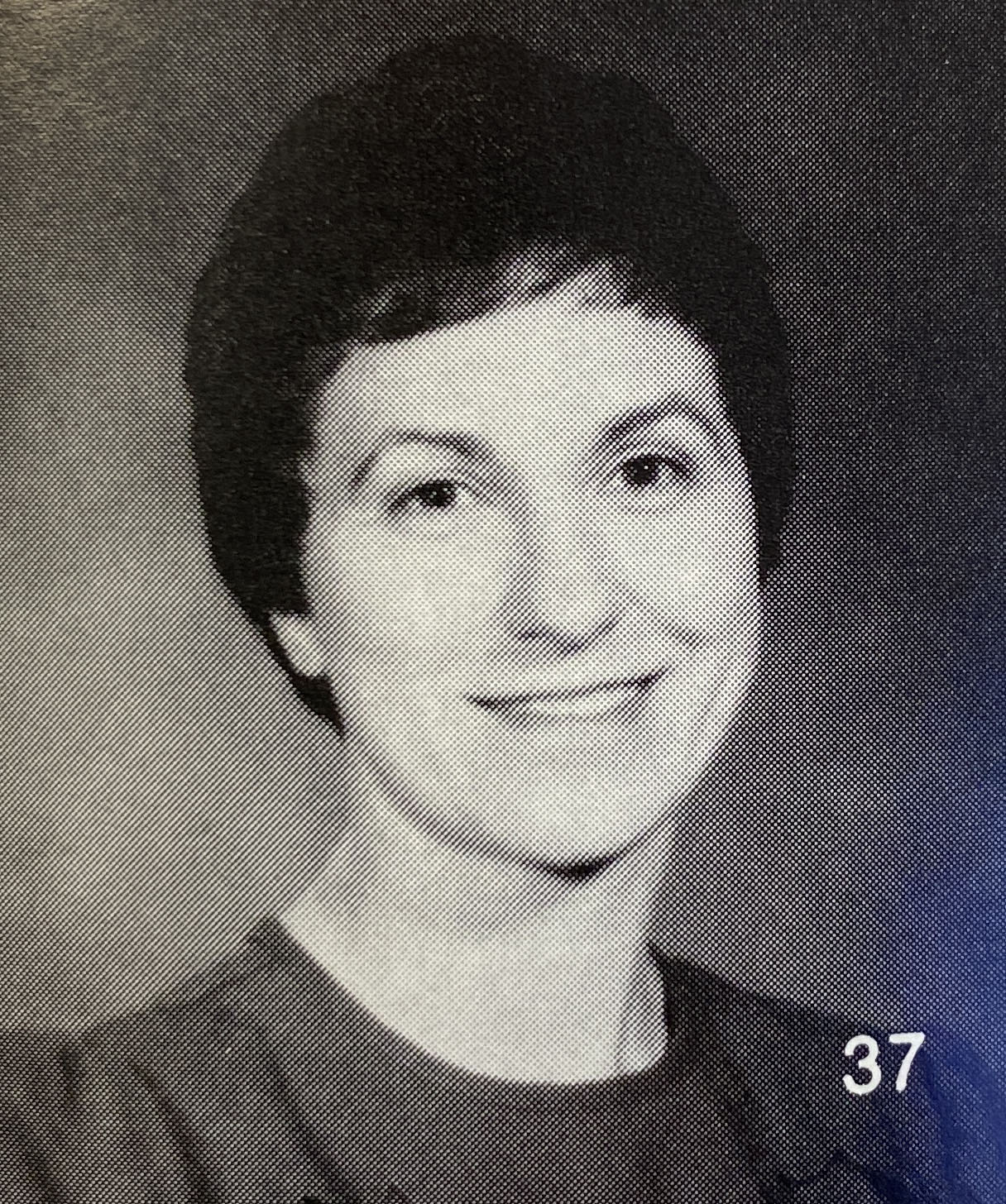

Cheryl Pillsbury, who started at MCHS in 1969, noted that it mirrored what was happening throughout the United States at the time.

“Because the school is really a microcosm of the outside world, progress in girls’ sports was slow,” Pillsbury, who also coached cheerleading, said. “Opportunities for women were few in the outside world, and so it was for girls in school. … I don’t recall any big rebellion. It just took a lot of convincing over a long period of time to get girls’ activities approved. Gradually, more things were added, and girls responded positively.”

Pillsbury explained that although people like Lyn Andracke — Minooka’s first girls basketball coach — and others had put forth a lot of effort to get these girls sports started, boys sports were still given top priority.

Since girls sports weren’t given as much attention, the coaches of those teams had to ask people to volunteer during games because they couldn’t afford more than one coach, Andracke said.

Financial Inequalities

And then there was pay.

“There was a dramatic difference in salaries,” said Pillsbury.

Before Title IX was passed, the difference in salaries between cheerleading and boys sports was evident. During the 1972-73 school year, the head football coach and head basketball each made $800, according to old teacher contracts provided by Pillsbury. The cheerleading coach for both football and wrestling combined made $200. The cheerleading coach for basketball also made $200.

Once girls teams started in 1973, there were still financial inequalities. For example, while coaches of girls volleyball and girls basketball each received $850 in 1978-79, the boys basketball coach received $1500 the same year. The salaries of a head boys and girls basketball coach wouldn’t even out until the 1985-86 school year when both were paid $2,400.

However, as early as the 1975-76 school year, both boys and girls track and field head coaches were paid the same.

Today, coaching salaries are bargained by the Minooka teachers’ union. They are grouped in different categories, with different salary amounts assigned to each category. The demands of coaching the sport, including the length of the sport’s season, are factored into determining the salary. In all cases today where a sport has a boys and a girls team, such as volleyball or soccer, the salaries are the same for both.

Also when they started, girls teams had much shorter seasons than the boys. While the girls basketball teams played five games during the 1977-78 season, the boys teams played 23. While this might account for the differences in salaries, it also shows the unequal number of opportunities the girls sports program faced. In the 1978-79 season, the girls played 16 games, and the boys played 24. The following year when the girls won the regional, it was the girls with 20 games and the boys 25.

Gaining Support

While not everything was equal, girls sports had people backing them. Parents were some of the first.

“We had a lot of support from the moms when we first started,” Andracke said.

Pillsbury said that most male coaches would congratulate the female athletes.

“Eventually, both male and female coaches supported each other and made an attempt to have their teams support each other,” Pillsbury said.

“Once we got by the initial resistance of women in sports, we always had people support us,” Andracke said.

In the 1980s, several more girls teams began at Minooka.

“It was nonexistent when I graduated (in 1973) and was fairly well established when I came back (to work as the MCHS librarian) in ’86,” said Carolyn Kinsella.

Cross country (fall 1982), the Arrowettes (fall 1986), and softball (spring 1987) were all added.

More men started coaching girls sports, as well. Wayne Greenbeck, who as a student at Minooka in the 1960s had admitted most guys didn’t think about girls playing sports, would eventually coach girls.

As a head boys basketball coach at Minooka, Greenbeck had a record of 195-189, four conference titles, and one regional championship over 15 years.

After the 1985-86 season, he was fired. But this didn’t stop his coaching career in basketball. The next fall, they asked him to be a girls coach.

His daughter Leah was going to be a freshman that year, and she wanted to play sports. He asked her how he should treat girls since he was new to coaching them.

“We don’t want to be treated like girls, we want to be treated like athletes,” she told him.

Greenbeck went on for six years coaching girls basketball. The girls would watch boys game films and criticize and learn from the boys since there were no girls films to watch. He was impressed at how fast they learned.

“Girls can respond quicker to a change than boys can,” Greenbeck said.

Making Progress

The 1990s saw even more girls sports added. Girls tennis began in the fall of 1992. Girls bowling, with Ken Maas as the first coach, started that same year, as well. Girls golf would begin in 1997. But some issues lingered.

Johnna Franklin, who teaches health, was the head girls volleyball coach at Minooka during the 1990s. She built a program that saw a team go to its first IHSA State Finals by the end of the decade. She had to fight for space, too.

“One day it was storming outside,” Franklin said, “and the football coach came into the gym where we were practicing and told us they needed to use the gym to practice football because the weather was too bad for them to be outside. When I told that coach that we would not be vacating the gym, he was shocked. I could tell that he was used to just having his own way for his boys team.”

Bleachers were more full, Franklin said, when the girls teams were winning.

“It wasn’t until the mid ’90s when our volleyball team starting to become highly competitive that we finally started to get some fans,” she said. “Today you see many boys coming to the girls games. In the early ’90s, boys didn’t really come to girls games.”

Leaving a Legacy

Minooka now has 12 athletic programs available for girls, and they have had a lot of success. Greenbeck was quick to point out some of Minooka’s individual state champs. Manette Cheshareck won the state championship in discus in 1987. Ashley Jones was a swimming state champion in the 200-yard individual medley in 2005. And Janile Rogers won the state long jump in 2014.

“We’ve probably had more girls go Division 1 over the years than boys,” Greenbeck said.

Nowadays the school has to make space for all the state trophies brought home by girls teams. Of Minooka’s 20 IHSA state sports trophies, nine were from girls teams. Not bad considering the boys athletic program had about a 30-year head start. MCHS has three IHSA sports state championship trophies, and two of those are by girls teams.

Girls bowling has three state trophies, all under coach Frank Yudzentis. They won their first state trophy during the 2004-05 season, placing third. Then they finished third again both in 2018-19 and 2019-20.

Girls cross country won the 3A state championship in 2015 with Kevin Gummerson as head coach. A year later, much of the team from the previous season returned to take home third at state.

In 2013, girls softball won the 4A state championship under coach Mark Brown.

The girls volleyball team brought home 4A state second-place trophies two years in a row in 2016 and 2017 with Carrie Prosek as head coach.

After competing under various organizations throughout the years, the Arrowettes began participating in the IHSA state series during the 2012-13 school year. Under coach Melissa Wallace, they brought home a third-place trophy from the state competition in 2019-20.

The fight to not only establish, but also grow girls sports at Minooka, has been nearly 50 years in the making. Franklin hopes it’s remembered.

“I think girls today take it for granted that they have school sports, and they have no knowledge of how hard girls had to fight to get sports.”

***************

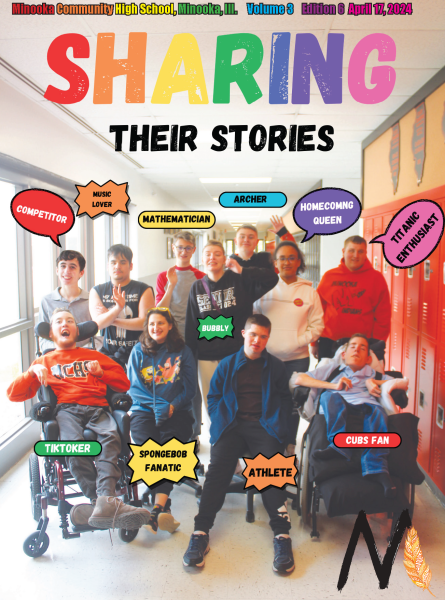

Much like the dawn of the girls athletics program itself, the telling of this story had its challenges. Students worked on it for more than a year, and most of the writing was done during the 2020 spring stay-at-home order because of the coronavirus pandemic.

The reporting of this story began in the spring of 2019. Cassidy Cundari and Andreana Haritopoulos, both 2019 graduates, interviewed Lyn Andracke and Glenda Smith for a story at the end of the 2019 school year. Cundari submitted a story a few days before graduation. It was wonderfully written, but there was more that could be told, and she agreed to pass the story to the next year’s journalists.

During February of 2020, the Media and Journalism 1 class began working on the story as part of the unit on writing features. They began working from the video recorded of Andracke’s interview and quotes from Smith. Then they sought out others who could help tell the story and collected interviews from several MCHS employees and students past and present. Cheryl Pillsbury, Johnna Franklin, and Sherry Schmidt were each interviewed by email. Carolyn Kinsella and Wayne Greenbeck both came to the school to be interviewed by the whole class. Their interviews were recorded by video. So was Ken Maas’s, who was still working as a campus monitor at South Campus. Ron Lehman returned a phone call after the spring stay-at-home order was already in place, and his interview was transcribed and provided to the whole class.

When the students began remote learning on March 17 during the stay-at-home order, little of this story had been written. Some sections were put together as an entire class, but for the most part, sections were divided up amongst the students. They wrote them, submitted them, and made corrections. Then as the sections were put together, they began editing. Some things were cut, some were combined, others had details added.

Final fact-checking for the story did not occur until fall 2020 when the school building was reopened and access to old yearbooks was available. Then three advanced Media & Journalism students — Meghan Angus, Leah Barys and Abbey Petric — did a fresh edit of the story and offered suggestions on how it would be published.

Sarah Lakomiak contributed much for the beginning of the story about the attitudes of girls athletics before Title IX. Emily Mepham and Macy Cornelius worked on the section on cheerleading. The part on the Girls Athletic Club was one of the few parts written before the stay-at-home order. It was written with the entire class giving input on what should be included and how it should be constructed.

The history of the IHSA was compiled by Bradley Gambosi, and the writing and research on Title IX was done by Joanna James and Jon Price. Miah Seloover focused her writing on the process of starting girls sports at Minooka. Lanie Baranoski wrote about the first girls soccer team, and Cornelius contributed to the first girls volleyball and track and field teams. Mikayla Thurman wrote the section on the first girls basketball team, with Lakomiak contributing Franklin’s experiences. Stephanie Elmore and Cundari wrote about the battle of gym space. Lily Powell and Mepham provided the section on inequalities once girls sports started, including coaching salaries. Emma Hall and Lakomiak wrote about girls athletics in the 1980s and ’90s. Jacob Checca compiled the information on the state trophies won by girls teams.

A couple days after part one of this series was published last week, Cheryl Pillsbury died. She worked at MCHS for 47 years as an English teacher, cheerleading coach, and department chair. During those 47 years and for this story, her contributions were both invaluable and selfless.

Bert Kooi • Nov 24, 2020 at 8:17 am

Coach Thomas and MCHS journalism students, awesome job telling the story of the history women’s athletics at Minooka HS. A story that needed to be told and is very relevant today. Reading about some of our past leaders in woman’s sports and leaders at MCHS was inspirational. We now have countless MCHS Women Athletes that have gone on to excel at the college level and beyond. In fact, just opened today’s paper to the headline, “Former Minooka Teammates lead NIU to 1st MAC cross country title”… Look how far we have come! Coach Thomas and MCHS journalism thanks for the research and thanks for sharing the story! MCHS Pride!

Glenda Smith • Nov 23, 2020 at 12:15 pm

This was an exceptional piece of journalism. Congratulations to all of those who contributed to this story that needed to be told. Your hard work is greatly aporeciated.